Novartis scheme can be a partnership with a difference.

Local partnership for Sybrava is a golden opportunity for Novartis to create a partnership with a difference and reimagine medicine for India and Indians.

I am sure some of you read this article with your morning tea, or the busier ones, on their social media feed. Either way - this is the news of the day that is making its rounds on all pharma WhatsApp groups. Here is me adding my $0.02 on the matter.

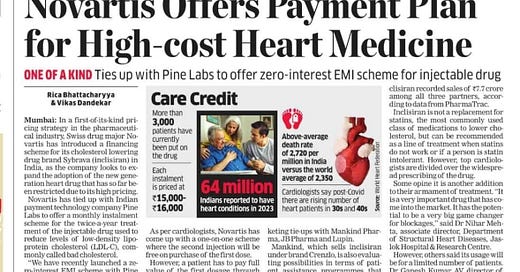

When Novartis announced a zero-interest EMI scheme for its advanced cholesterol-lowering injection Sybrava (inclisiran) in India, the move was lauded by some as a progressive step toward improving access to expensive, life-saving therapies. Designed to be administered just twice a year, inclisiran represents a new generation of treatments for patients with uncontrolled LDL cholesterol, particularly those at high risk of cardiovascular events.

But beneath the surface of this patient-friendly initiative lies a bigger question: Is this really a sustainable model for affordability, or does it simply create the illusion of access?

Sybrava is a high-cost biologic, and for patients in India — where out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure is among the highest in the world — the upfront price tag can be prohibitive. An EMI scheme softens that blow, allowing patients to pay over time without incurring additional interest.

In this case, Sybrava costs Rs. 1.2 lakhs/dose and is needed every 6 months or so, for life. This means an interest-free EMI of Rs. 15-16,000. This is not insignificant. In a healthcare system where insurance coverage is limited, and where many life-saving drugs are paid for in cash, such schemes can improve short-term affordability and boost treatment initiation rates, especially among middle-class patients in urban centres. Moreover, by ensuring financial flexibility, Novartis may also help improve long-term adherence — a critical factor in chronic disease management, where drop-off rates are often high.

However, there are limits to financial engineering too. An EMI scheme does not reduce the actual cost of the drug — it only spreads it out. For a medication that could cost Rs 2,40,000 or more per year, even a zero-interest EMI is not a viable solution for the average Indian.

At best, this scheme makes the drug accessible to a narrow sliver of the population: salaried, insured, and already relatively health-literate patients. For the vast majority of Indians — especially those in semi-urban or rural settings — this is not affordability. It’s financial gymnastics.

The Novartis initiative reflects a broader challenge in Indian healthcare: the gap between affordability and access.

While pharma companies often introduce patient-support programs, copay assistance, or instalment options, these mechanisms remain demand-side solutions. They do not address supply-side issues such as:

High base prices of patented or innovative medicines

Lack of local manufacturing or tech transfers

Inclusion in national or state-level public health programs

Government pricing negotiation or subsidy schemes

In contrast, game-changing access initiatives — such as Gilead's voluntary licensing of hepatitis C drugs to Indian generics manufacturers — brought down the price of treatment by over 95% and changed the public health landscape. Novartis could think on these lines.

In this case Novartis is co-marketing the product with Lupin, JB Pharma and Mankind. The EMI scheme, however, is applicable to Novartis’ brand alone. It is expected that the partners may announce their own patient assistance programs in due course. So, the price stays the same despite 4 companies (Novartis and 3 partners) selling it in India. Should the partnership focus on EMIs or other “assistance programs” or do something more to really create affordability and access?

An EMI scheme might inadvertently reinforce a two-tier healthcare system — where the urban affluent can access cutting-edge therapies through financing schemes, and the rest are left behind. Over time, this can exacerbate health disparities, particularly in chronic diseases like cardiovascular conditions, which already disproportionately affect lower-income populations. True affordability must mean universal access, not just payment convenience for a few.

That said, Novartis is serious about healthcare access. India MD, Amitabh Dube recently expressed his vision on Viksit Bharat at 2047 and wrote about what it would take Indian industry to hit $450 billion. This could be a peek into the future.

In line with this vision, one would expect that Novartis (and its partners) would work on the following:

Inclusion in government insurance schemes like Ayushman Bharat or CGHS

Collaborations with state governments for subsidized rollouts

Investment in local manufacturing to lower production costs

Outcomes-based pricing tied to public health goals

These strategies, while more complex, offer more equitable, scalable, and sustainable solutions than EMI plans alone.

To be sure, the EMI scheme for Sybrava is not meaningless. It may help a subset of patients start and adhere to treatment. But it is, fundamentally, a commercial innovation, not a breakthrough. It is at best, a step, not a solution. Without structural reforms to how medicines are priced, procured, and distributed in India, such efforts risk becoming more about optics than impact. In the long run, India needs pricing transparency, health system integration, and a commitment to universal coverage — not just creative financing.

Given global pressure, if Novartis cannot do it alone, it needs to encourage local thinking in its partnership, if the patient is indeed at the centre of everything. That would indeed be reimagining medicine for India and Indians.

Good comprehensive insightful write up.

I know you are aware, that the idea of giving support for high cost treatment with payment plans is not new. Some pharma companies have tried it earlier for critical care and speciality medicines. Though none have gone to the press with such an announcement. These plans have mostly been non-starters. Like you said for a chronic care drug the cost still remains high, even if it's divided as EMI, thereby affordability remains a challenge. For acute care or critical care medicine the time for approval and paper work to get the support has dissuaded most patients and hospitals. In my experience not more than 5% patients took the support of such a payment plan. Please note, my experience is limited to a couple of drugs.

Sadly, only local manufacturing and loss of exclusivity, read reduced cost, will certainly give significantly improved access in a country like India.

Interesting perspective Salil, but I would like to differ from your perspective a bit. There will surely be number of patients who would like to use emi option, speaking out of my field and bit personal experience